|

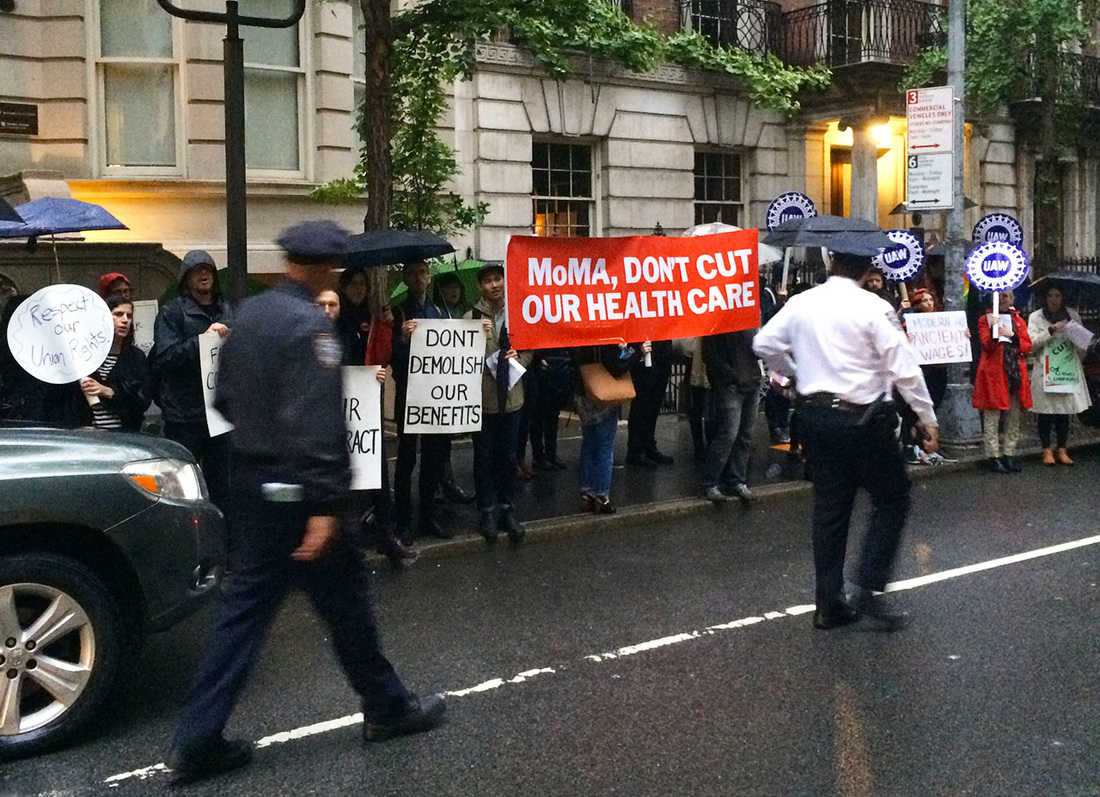

Hi all, Allison here with a little reflection on HAND FOOT FIZZLE FACE in relation to WORK. Specifically, my work, or rather, the work for which I earn a modest salary at the Museum of Modern Art. Before I begin, let me just say that I truly value the work that I do, the people with whom I work, and the fact that I’m lucky enough to work at one of a very few unionized cultural institutions. That being said, my union, Local 2110, Professional and Administrative Staff Association of The Museum of Modern Art (PASTA-MoMA), is involved in a rather hairy contract negotiation with museum management. At first I was merely crestfallen to hear that the organization for which I’m able to work partially because it offers excellent health benefits was threatening to severely cut those benefits - until I realized how deeply my feelings on the matter were beginning to align with HFFF. Then I was...more productively crestfallen. The thing is, I’ve only been at the MoMA for about 9 months, but at every single staff meeting we’ve heard that this is the museum’s best year ever, that the endowment is at an incredible all-time high, that retail sales are through the roof, etc. To suddenly hear a change of tune, right as our contract runs out, that things are inexplicably maybe going to start looking grim, has created the impression that not only is our work undervalued, but so too are our critical thinking abilities. Then, to threaten our health care specifically, to insist that we shoulder a new burden that threatens our medical care without a commensurate wage increase, feels like a direct assault on our bodies. Bodies, minds, work. Bodies, minds, work - and art. Specifically, some of the most admired, expensive art in the world.  So here we are, aware of our suddenly more fragile-seeming bodies, tasked with the care of this massive collection of incredible, beautiful, moving objects. I mostly sit in my office tinkering with the collections database, but sometimes I have the great pleasure of entering the galleries and spending some time with the pieces it catalogs. It’s startling to find that, when you realize that the institution partially responsible for the fame and value of these objects is trying to get your work/time/body at a discount (and during a flush year at that), the power of these pieces - well - it fizzles. They fizzle. They’re just sitting there being worth more than your health, and their emotional resonance flattens. Sure, I believe that art can have immense value, and that we mere humans use dollars to demonstrate this concept, and all of this is no surprise, but suddenly the strangeness of Foirades/Fizzles - brief meditations on suffering and the human body wrapped in a luxurious, exorbitant package - started to vibrate in my own body. My own body which may end up forgoing that foot surgery I should probably have - it’s not really that necessary and will only prevent my knees from decaying too fast which is probably a fool’s errand after all, right? Maybe a new building to share more of the MoMA’s collection with the public is more important than offsetting the cost of my partner’s sure-to-collapse-someday lung - or maybe it does more damage to the work and the artists’ intentions to finance a shiny new building (or package, if you will) on the backs of workers. I’m under the impression that there isn’t too much union-busting, anti-labor art in the collection but hey, what do I know. On the other hand, maybe the more glamorous, expensive, and anti-labor the museum becomes, and the more at odds with some of the art/themes contained therein, the more new art can spring from the crackling cognitive dissonance of that juxtaposition - and so on...prodding...calibrating...fizzling...fizzling...fizzling...

0 Comments

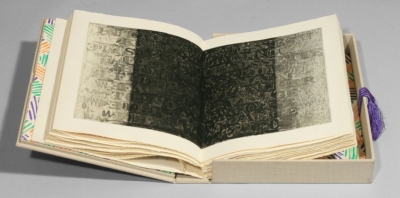

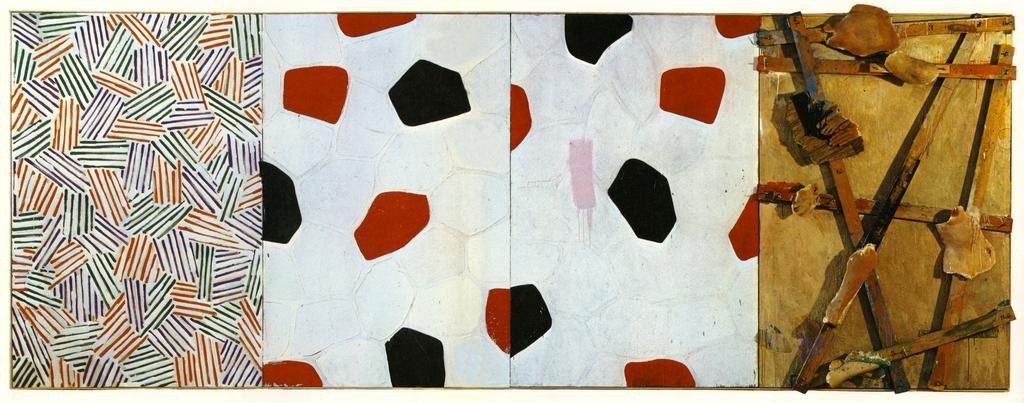

Although the arranged marriage between Jasper Johns and Samuel Beckett that produced the art book Foirades/Fizzles was not a match made in heaven, we can guess why publisher Vera Lindsay thought it might be a good idea. Employing a variety of media including painting, various forms of printmaking, and collage, Johns’ work regularly recycles materials and imagery from trash heaps, popular cultural, and his own previous creations. Says Joan Rothfuss, “he establishes a motif, most often in a painting, and then reworks it again and again, changing media, scale, or system, just to see what happens to it.” Beckett’s prose work displays a similarly obsessive repetition, with facsimiles of phrases and characters recurring as the author circled around themes of human loneliness and isolation. S.E. Gontarski describes Beckett body of work as a process of distillation through which “novels were often reduced to stories, stories pared to fragments, first abandoned then unabandoned and ‘completed’ through the act of publication.” When Lindsay first paired the two artists in 1972, Beckett suggested that they work with the text of Waiting for Godot. Johns rejected the idea, preferring to work with unpublished (i.e. uncompleted) material (we can imagine Beckett’s words fizzling in that unbridgeable gulf in one of the few photos of the pair). Instead, Beckett sent Johns collection of eight prose poems that were eventually published on their own 1976, the same year Petersburg Press produced 250 limited edition copies of Foirades/Fizzles. So much for using exclusive, unpublished work. Johns selected five of Beckett’s eight fizzles, and then turned to a previous creation of his own. Untitled (1972) is a 6 foot tall panorama of four discrete panels—one of a crosshatching motif that appears in much of Johns’ repertoire, two with flagstone imagery, and a fourth with plaster casts of human body parts mounted on wooden slats and affixed to the canvas. For the Petersburg book, Johns created a series of etchings that refract and rearrange the elements of Untitled (1972): variations on the crosshatchings, obsessively re-printed flagstones, and the body parts of the fourth panel rendered with different textures, contrasts, and scales. To introduce each fizzle, Johns also created stencils of the numbers one through five, a motif that he had been reshaping in paintings and prints for the past 10 years. Scholars have devoted reams of paper to naming the precise logic that guided Johns in his obsessive duplication of the images in Foirades/Fizzles. “Above all,” says Richard Field, “Johns wished to demonstrate that the four panels [of Untitled (1972)] were not a totally arbitrary assemblage.” As if somehow, by creating variations on these motifs and by pairing them with further discontinuous texts, the reader might be able to invent the pathways that traverse the gulf between the four discrete panels. But whatever hope of clear insight we may have, the book refuses to supply the satisfying synthesis. As Rothfuss notes, when we linger too long amidst the handmade pages of Foirades/Fizzles, “we are left with a vague sense of something amiss.” The three slideshows in the blog post represent an attempt to trace down the echoes of the fizzled collaboration between Johns and Beckett: the three fizzles omitted from Foirades/Fizzles, paired with other Johns experiments with the imagery from Untitled (1972) and from his settings of numbers. They remind us that the sense of something amiss generated within Foirades/Fizzles also reverberates outwards, recycled again and again in image and text. Or, as one of the fizzles describes: "Then the echo is heard, as loud at first as the sound that woke it and repeated sometimes a good score of times, each time a little weaker, no, sometimes louder than the time before, till finally it dies away." |

Cover image by Carol Rosegg

Archives

December 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed